For the past several years, veterinarians and pharmaceutical companies have teamed up in a marketing campaign to frighten pet guardians into giving year-round heartworm preventatives to both dogs and cats. The campaign has really ramped up this year. They say they’re doing this to improve protection for individual pets, but we need to take a closer look to discover the truth.

How do pets get heartworms?

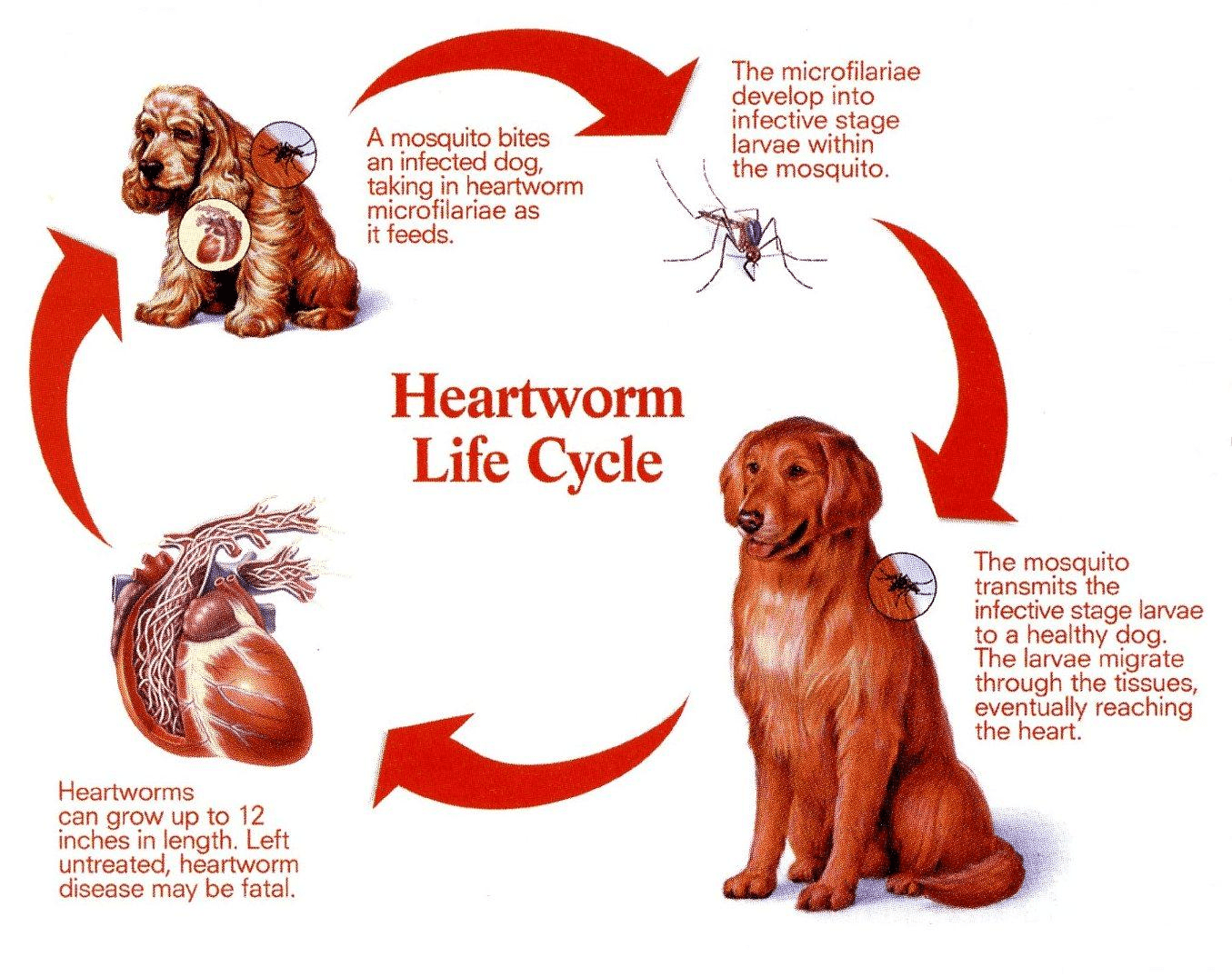

Heartworms are transmitted by mosquitoes. Tiny heartworm larvae, called microfilaria, circulate in the blood, and are sucked up by the bug when it feeds on an infected host animal; for heartworms, their natural host is the dog. Once inside the mosquito, the larvae must develop through more stages before they can infect another dog. For that to occur, outside temperatures must remain above 57 degrees F, day and night, for a minimum of 8 days. The warmer the temperature, the faster the larvae will mature. If the temperature drops below that critical level, larvae development will stop; but the larvae don’t die—development will re-start at the same point when the weather warms back up. Larvae reach their infective stage in 8 to 30 days (the latter being the entire lifespan of the average mosquito).

When an infected mosquito bites a dog or cat, the heartworm microfilaria are deposited on the skin, where they crawl into the bite wound and enter the bloodstream. Inside the body, they get ready to “settle down and raise a family.” In dogs, the heartworm’s natural host, the larvae migrate to the heart and eventually develop into adult worms, reproduce, fill the blood with microfilaria, and pass it on to the next mosquito. The maturation process takes 6-7 months.

What do heartworms do?

Once in the bloodstream, the microfilaria migrate to the right side of the heart and attach there, where they can grow into adulthood. According to the American Heartworm Society, “Clinical signs of heartworm disease may not be recognized in the early stages, as the number of heartworms in an animal tends to accumulate gradually over a period of months and sometimes years and after repeated mosquito bites. Recently infected dogs may exhibit no signs of the disease, while heavily infected dogs may eventually show clinical signs, including a mild, persistent cough, reluctance to move or exercise, fatigue after only moderate exercise, reduced appetite and weight loss.” It takes microfilaria about 6-7 months to mature into adults and start reproducing. Clinical signs are not typically seen before that. Adult worms can live up to 7 years in the dog.

In cats, adult worms can develop, but they cannot reproduce; they take about 9 months to mature, and they tend to live only a year or two. However, adult heartworms are about a foot long, so it only takes 1 or 2 to fill up a cat’s tiny heart and cause serious problems.

As it turns out, cats have pretty good defenses of their own. In 80% of cases, the cat’s own immune system kills the larvae and clears the infection. Nevertheless, microfilaria can still cause significant inflammation in the lungs, even in cats who never show any signs of infection. Feline heartworms may be commonly misdiagnosed as asthma or bronchitis, when it is actually Heartworm Associated Respiratory Disease (HARD). Also, for the 20% of cats who do become persistently infected, severe respiratory and/or cardiac disease can occur. Heartworms have been diagnosed even in cats who spend 100% of their time indoors.

Treatment

Treatment of a mature heartworm infection can be very dangerous. When the arsenic-based drug is given to an infected dog, the massive die-off of the worms can cause severe inflammation and even respiratory failure. Not all dogs survive treatment. Clearly, prevention is the best option! Alternatively, many veterinarians advocate simply giving the regular heartworm preventative to kill off any microfilaria already present and keep newly deposited larvae from developing, while waiting for the adult worms to die. This may be a more practical alternative for cats, or for dogs that do not have a severe infestation.

Seasonal vs. year-round protection

Except for a the warmest parts of the U.S. (mainly in the southeast), heartworms are a completely seasonal problem. There is no reason to give heartworm medicine to most pets year-round (except to make money for those who make and sell it!).

In many areas of the country (northern and mountain states, for instance), such warm temperatures simply don’t exist for most of the year, and sustained warm temperatures don’t occur until at least June. In fact, only in Florida and south Texas is year-round heartworm transmission possible. Within 150 miles of the Gulf Coast, heartworm risk exists 9 months out of the year. In the rest of the country, heartworm transmission is possible between 3 and 7 months out of the year. Hawaii and Alaska have each had a few cases of canine heartworm, but the incidence in those states is very low.

It should be obvious that during seasons where there are no mosquitoes, there is no risk of heartworm. Evidently that little fact escaped the attention of the veterinarian who prescribed heartworm protection—in December–for a puppy living high in the Colorado mountains. At that altitude, temperatures are never warm enough for heartworms!

A debate about when to give heartworm preventatives was published in an April 2009 journal article (“Ask the Expert: Year-Round Heartworm Prevention: Two Viewpoints,” by Dwight Bowman and James Lok, published in NAVC Clinician’s Brief, the official publication of the North American Veterinary Conference, 2009/04/01). Both authors are university professors in parasitology.

The argument presented by Dr. Bowman in favor of year-round heartworm medication focused on just two points: (1) the speculation that “scenarios can arise where transmission may occur in cooler climates in the ‘off season;’ and (2) the completely unrelated issue of prevention of internal parasites by additional drugs added to the heartworm preventative.

Arguing on the other side, Dr. Lok lays out the case for appropriate seasonal control, and concludes, “Besides incurring unnecessary costs for the client, indiscriminate application of broad-spectrum medications can engender further confusion about the primary imperative for these medications—heartworm prevention—and when they are most crucial—during the season of heartworm transmission.” Of course, if in any given year the weather is unseasonably warm for long enough, exceptions to those recommendations should be made.

Having looked at both sides of the issue, I have to agree with those who suggest that giving year-round treatment to animals in states where year-round transmission does not occur is doing an injustice to both the animals being given drugs they don’t need, as well as the pocketbooks of their guardians. This argument is rarely presented since the drug companies have the resources to widely promote their views (and products) to consumers as well as veterinarians.

Heartworm prevention

The most common preventative drugs for heartworm are Ivermectin (Heartguard®), Milbemycin (Interceptor®) and Selamectin (Revolution®). While these drugs are generally safe and effective, there are always exceptions. Toxicity associated with Ivermectin include depression, ataxia (balance problems or unsteady walk), and blindness, but these are uncommon at the low doses used in heartworm preventatives. Ivermectin should be used with caution in collies and related breeds such as Old English Sheep dogs and Australian Shepherds, who are more sensitive to the drug’s neurological effects. Milbemycin, the most common alternative drug for Collie breeds, can cause depression/lethargy, vomiting, ataxia, anorexia, diarrhea, convulsions, weakness and hyper salivation. Selamectin is also used to treat ear mites and some worms; adverse reactions include hair loss at the site of application, diarrhea, vomiting, muscle tremors, anorexia, lethargy, salivation, rapid breathing, and contact allergy.

Another serious and growing problem is resistance of heartworms to these drugs. This means that we are selecting for super worms that will be able to survive and grow even in animals on heartworm preventatives. As with all cases of resistance, the correct response is to reduce use of the drug and reserve it only for when it is absolutely necessary. Unfortunately, the veterinary profession and drug industries are continuing to call for all pets to be on medications all year round. This is bad science, and it is bad policy.

Only Natural Pet HW Protect Herbal Formula is a natural product intended for use as a preventative to be used during mosquito season as part of a comprehensive heartworm control program. The formula was designed with two objectives, using herbs that work together to reduce the likelihood of mosquito bites to lower your pet’s risk of becoming infected, and to help eliminate existing larvae-stage parasites in the bloodstream. This tincture was developed to help prevent heartworm infestation using extracts of herbs well known for their mosquito repelling properties, and others well known for their anti-parasitic properties. Using an insect repellent like Only Natural Pet Herbal Defense Spray may also help prevent heartworms by keeping mosquitoes away from pets when they are outside.

An herbal approach to heartworm prevention is not like a traditional heartworm pharmaceutical preventative, which chemically kills all heartworm larvae, but it may be an effective and more natural method to prevent heartworm infection. Consistent dosing is essential for proper protection, along with heartworm testing at least every 6 months.

Summary

1) The temperature needs to stay above 57 degrees for 8 to 30 days.

2) A mosquito has to bite a dog that already has microfilaria in its bloodstream.

3) That mosquito has to then bite your dog or cat 8-30 days later.

4) You must give the heartworm preventative medication within 6 weeks of mosquito bite to kill microfilaria in the blood and prevent the larvae from growing to adulthood.

References:

Knight DH, Lok JB. Seasonality of heartworm infections and implications for chemoprophylaxis. Clinic Tech Small Animal Practice. 1998 May;13(2):77-82.

0 Comments